This speaks to an experience that’s just tight. Unlike Ubisoft’s blockbuster open worlds, pleasure derives from focusing on the foreground rather than a vista.

#TOEM OF UND SERIES#

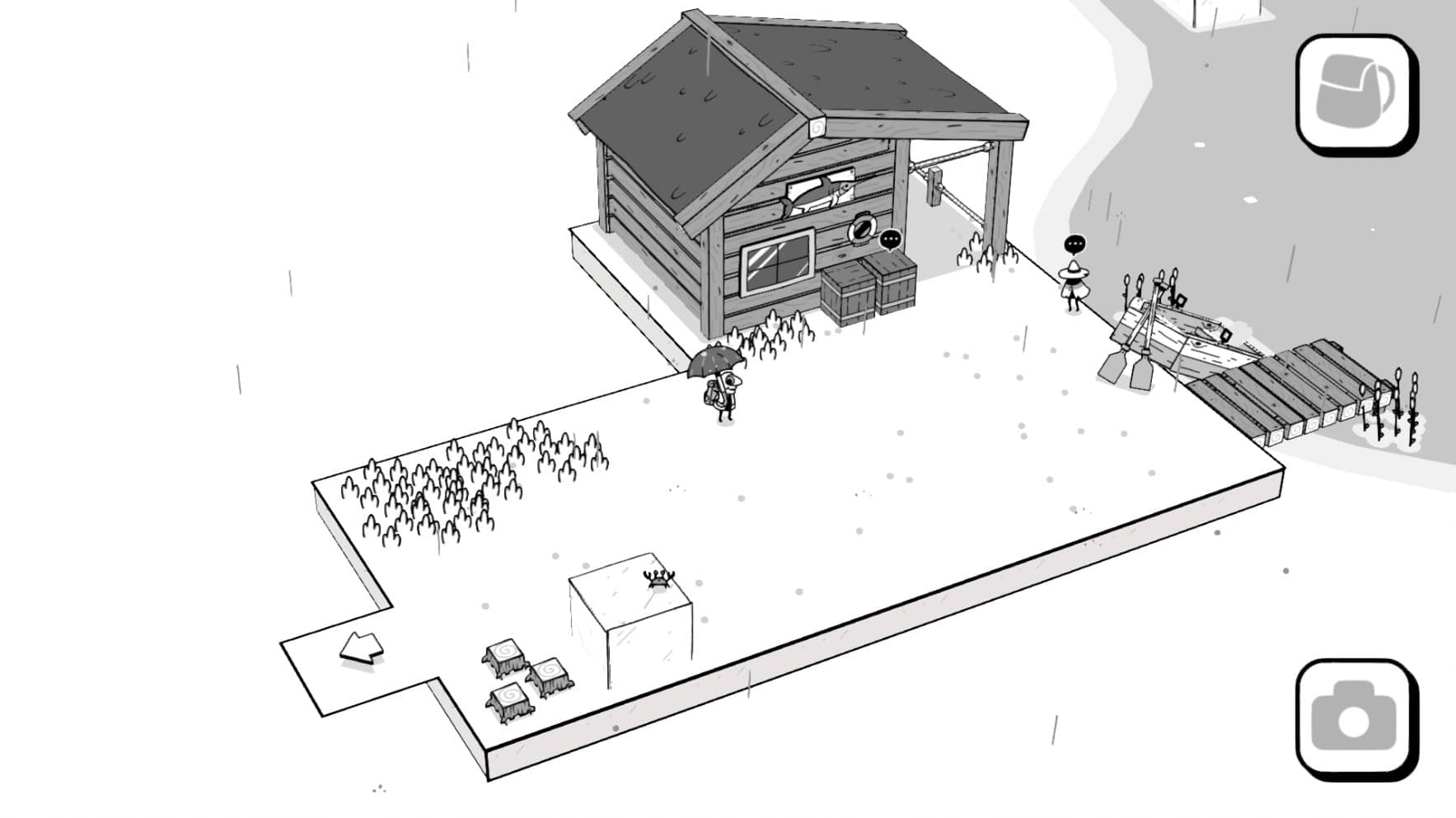

These aren’t single, unbroken spaces but a series of modular environments that fit together like puzzle pieces. This compact, deliberate design extends to the levels which whisk you to a summer camp, beach resort, bustling city, and snow-capped mountain. It gives you the freedom to approach tasks in any order you like but lacks the unending horizons and cluttered maps that have come to define it. Like A Short Hike, Toem distills open world video games down to their joyful essence, even as it eschews many of the genre’s hallmarks.

You go from looking down at your character to looking around. Each time you pull your old-school camera out, this tension is resolved beautifully. As you explore the game’s diorama environments, there’s always the nagging sense that you’re seeing less than you would like, that you should be able to peer beyond the top of the isometric viewpoint. You’ll photograph a lot of stuff in Toem because this is a checklist game at its heart, one filled with cute non-playable characters who need you to take a particular shot-graffiti, skateboarders, a DJing moose. What’s surprising is that this mechanic doesn’t get old. For the first time, you see her bespectacled 2D form in front of you alongside the cozy environment. By pressing triangle, the zoomed-out viewpoint snaps to first-person. She asks you to photograph her, and it’s here that the game’s central mechanic is revealed. Her home is rendered in unfussy hand-drawn style-thick black lines, bold shapes. And come to the book launch and the opening of the Tokyo Totem on October 30th.Toem begins in your grandma’s house on what feels like one of those endless summer days. Learn more about this book, and check out the general information, table of contents, introduction and some selected sample material from the book. Whitelaw, bathhouse connoisseur Greg Dvorak and many others. Amongst your ‘guides’ are social design researcher Atsushi Miura, Tokyo Urban Basin Society president Norihisa Minagawa, architect Julian Worrall, architect Julian Worrall, artist Arne Hendriks, editor Kohei Fukazawa, architect Yasutaka Yoshimura, visual artist Jan Rothuizen, urbanism professor Christian Dimmer, anthropologist Gavin H. In a way each author is a guide, and thus this guide book is reality 46 guidebooks. You may look at the city through the eyes of a bathhouse connoisseur, a host, an architect, a topographer, a flaneur, a konbini anthropologist, a foreigner, an artist or a child. Each contribution let’s you experience a different city. It is called a guide, not because it helps you to find places to see, or places to eat or drink, but because it helps you to read and see the city differently.

Everybody’s efforts resulted in the essay’s, maps, photo essay’s, collage’s, poem’s, manga’s, illustrations and observation’s that have been collected in this book that is hard to categorize. This eclectic group grew from an international urban research and exploration workshop on Tokyo organised by Amsterdam-based studio Monnik and hosted by Tokyo’s SHIBAURA HOUSE exactly 3 years ago, on 30 October 2012. What they have in common is their interest and fascination with cities, and in particular Tokyo’s urban culture. This publication is the result of a collaboration between international and Japanese authors and makers from various disciplines, ranging from art to social science and from urban studies to design.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)